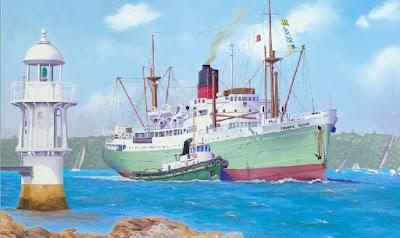

April 1968 – one of the hottest days on record for this time of the year in Brisbane. A smart-looking grey-green ship, a plume of fine white smoke wafting from its orange funnel, slips her moorings from Hamilton Wharf and slowly drifts towards the middle of a listless Brisbane River. At a ship’s length or more from her berth, a couple of small brawny tugs gently haul on her bow, turning her through 180 degrees until she faces downstream towards Moreton Bay and the mouth of the river, some 30 km away. The remains of a few paper streamers which had, until a minute ago connected passengers and well-wishers on the shore are now floating in the wind against the outward side of the ship or drifting into the water to be consumed by the wash from the large bronze four-bladed

propeller which has begun purposefully churning a metre below the surface of the water.

This is the cargo passenger vessel SS Francis Drake. With 120 passengers aboard and 150 tons of refrigerated cargo, she is bound for the Philippines on the first leg of her scheduled two-month round-trip to the Far East.

I’m seeing none of this – I’m on the bottom plates of the engine room, several metres below the water line, alongside my new shipmate, Fifth Engineer Jimmy Leong as we stand at the controls of the large Vickers Armstrong steam turbine engine which will push us along, once we are in the open sea at a comfortable 15 knots.

It’s hotter down here. Four inches of insulated lagging

doesn’t stop radiant heat from the pipes delivering superheated steam from the large water tube boilers above my head to the high-pressure turbine of the main engine. Like ships’ engine rooms everywhere, it is always a good deal warmer here than on the bridge.

I’m the other Fifth Engineer and I stand next to Jimmy watching his every move in what, for the moment, is a spotless white boilersuit. Jimmy is more senior than me and has charge of the watch, a fact for which I am most grateful, this being my first “SS” after previously serving only on “MVs”.

After the compact single deck machine space of MV Viajero,

the multi-levelled engine room here is cavernous. Alongside the turbine propulsion unit, the space also houses auxiliary turbine-operated AC generators, refrigerating compressors, air compressors, purifiers and a condenser which converts low pressure exhaust steam from the turbine to condensate which is returned as feedwater to the boilers.

There is a lot for me to learn about steam propulsion, not

the least of which is that unlike the internal combustion cycle which describes a diesel engine, the steam turbine combustion takes place externally in the boilers. All that aside, and in contrast to some of the other ships I’ve been on over the past couple of years, I’m in a clean engine room, no less noisy than any other I’ve seen, with a high-pitched gear box connected to the propeller shaft whining in my ears and making conversation almost impossible without shouting directly into someone’s ear – but most definitely cleaner – and no fuel valves!

So what brings me here?

Three months ashore, working as an estimator for a large engineering construction company in downtown Brisbane had been enough for me. After a couple of years sailing around the world on British cargo ships, which included a spectacular year on the Amazon River, I clearly wasn’t ready to settle down and behave like a grownup, so when the opportunity arose, via a lunchtime stroll into the offices of H C Sleigh the operators of Dominion Line, I jumped at it and here I am.

There is a lot more to get used to than just the technical

stuff. The wearing of uniforms (not just one) is a far cry from the relaxed attitude of Baron Jedburgh and Viajero where the focus was on comfort and minimal trips to the ship’s laundry.

I’m also getting used to more people on board. In addition

to the passengers, we have a large crew which includes deck officers,

engineers, catering staff, administrators and passenger service providers plus

a Hong Kong Chinese crew. Over the course of the next year, there are regular changes to personnel as crew members take leave, or transfer to other ships in the fleet, so I will

never get to know everyone the way I have done on previous ships. In my whole time on board, I don’t recall exchanging a single word with the Ship’s Captain or the Chief Mate.

We have our own engineer’s mess, where staff on duty are

catered for – the rules being that in order to use the duty mess you must actually

be on duty, and you must be wearing a clean boilersuit. I was not the first person

to be turned away from the mess for looking like I had just come out from under

the bilge plates – which I probably had. Otherwise all ship’s officers are

required in full uniform in the ship’s dining room at their assigned tables

which includes passengers – so best behaviour, best table manners.

Francis Drake is anything but a young ship. Built in

1947 at the Vickers Armstrong shipyard in Newcastle, UK as the SS Nova

Scotia for the Furness Warren Line she operated for 15 years alongside her

sister ship SS Newfoundland between Liverpool and the Canadian ports of

Halifax, New Brunswick and St John’s, Newfoundland. The two vessels were sold

to Dominion Navigation Co in the early 1960s and after extensive fitout and

modification which included extended accommodation, air-conditioning and capacity for refrigerated cargo, they were relaunched into

service in the Far East and Australia as Francis Drake and George

Anson.

The ship’s operator and my employer is H C Sleigh & Co,

an Australian firm of shipowners and petroleum products, mostly known for the

large merino sheep logo which identifies the Golden Fleece brand of products.

She’s no youngster, but thanks to the refit a couple of

years ago, she’s clean and seaworthy and despite the requirement for a little

more spit and polish than I’m used to, I no longer have to think about putting

condensed milk straight from the can into my tea when the fresh milk runs out

as we did on Baron Jedburgh.

As I mentioned earlier, wearing of uniform is a requirement

whenever we’re in any of the public areas - number nines, number tens, mess

undress; I’m rather surprised they didn’t ask me to wear a sword!

I’m the only new

person on board. I’m replacing the third

engineer who has been transferred to another ship. As a result, all the other

engineers were promoted which left a requirement for a junior watchkeeping

fiver – me. They are a good bunch. The third and fourth engineers are from Hong

Kong while Jimmy, my fellow fifth engineer on the 4 to 8 watch is Singaporean.

Graham, the second engineer is not much older than me. A

softly spoken, Melbournian, this is his first voyage as second, but not his

first trip on Fanny Duck as the ship is affectionately known. He’s a talented engineer, knows the ship well

and has a relaxed and calming manner which is in stark contrast to his boss,

the Chief Engineer who on the rare occasions when he is seen, looks like he’s

ready to fire someone – we keep out of his way.

There are two other characters in the engineering

accommodation. My next-door neighbour on one side is the Electrical Engineer,

Jimmy Warburton. Jimmy is a cool guy, whose

prized possession is a state of the art, reel to reel audio system which takes

up most of the space on his desk and is a source of envy to all. Jimmy is also

a passionate St Kilda supporter and no hospitality session with Jimmy is

complete without tales of Allan Jeans, Carl Ditterich and the 1966 Premiership.

My other neighbour is the Refrigeration Engineer – a curly-haired

former Orient Line graduate from Plymouth.

Bob Pope will become a good friend and after our sea-faring days, we

will, at various times be work colleagues, housemates and fellow-travellers through

a European winter in an old 3-litre Rover. We will later live within a

few hundred yards of each other in the same Sydney suburb where we’ll enjoy

many family barbecues reminiscing and telling tall stories about these times. All

that is in the future, today Bob is another cool guy who has an extensive

collection of knock-off vinyl LPs from Taiwan with a strong focus on The

Rolling Stones, The Who and Joe Cocker – all good stuff. Bob recently transferred to Francis Drake from

her sister ship George Anson, so he already knows his way around, and quickly

introduces me to the ship’s many social activities.

Finally, in introducing my shipmates I can’t forget the

female members of crew. The ship’s executive officers includes a nursing

sister, a writer (who is really an assistant purser), a shopkeeper and a

hairdresser. They are a cheerful and friendly group and, as I learn over the

next few months, a pleasure to sail with and great fun on a shore run.

Unlike a cargo tramp, we know exactly where we’re going and

when we’ll be there. Starting the voyage from her home port of Melbourne a

couple of weeks before I joined, she stopped on the way for two or three days in

Sydney, before heading north to Brisbane the last of her Australian ports. She

is now enroute to Manila, Hong Kong, Keelung (Taiwan) and Yokohama

(Japan). The return trip south stops at

Guam and Rabaul before heading back home to Melbourne and preparation for the

next round trip.

I never actually intended that these stories turn into a series

of travelogues. My focus has been in seeking to paint a picture of life on

board, to talk of the many wonderful characters I enjoyed sailing with (and one

or two I didn’t) and in some small way share a few of the experiences as they

happened.

Having said that, I think there’s more to tell, but I don’t want to test your patience so I’m going to leave it for my next chapter – which I’m looking forward to writing (I hope you share the sentiment).

Thanks for this, Mike. Absolutely fascinating to learn more of your life's journey(s).

ReplyDeleteGreat read!

ReplyDeleteReally enjoyed!

ReplyDeleteI loved reading this, Dad!

ReplyDelete